The neocortex: the organ that occupies ~80% volume of the brain while consuming ~20 Watts. In his book, A Thousand Brains: A New Theory of Intelligence by Jeff Hawkins the author tries to illuminate how the cognitive sausage is made by looking at a lot of neuroscience clues and trying to piece them together into a new theory of intelligence.

I’ll try to summarize and make sense of his theory here, the way I understood it, and hope it creates excitement for others who are thinking of reading the book. I highly recommend reading the book yourself and I must warn you that I’m not a neuroscientist or AI person. I’m a software engineer that has an interest in these topics.

Before I start, please note that the book is split into two sections - I’ll focus on the first section because that’s where my main interests lie. The second section of the book is diving into the future of humanity, AI safety, space exploration, and many more interesting topics. I enjoyed all these, but I admit, I wanted more juicy neocortex meat.

I’ve been a fan of Jeff Hawkins since ~2009 when I read his first book, On Intelligence - his HTM theory and what it implied was inspiring to say the least. It was the first attempt that I heard of that tried to create a theory of how the neocortex works. The second book expands on the HTM and attempts to complete it. Armed with a decade+ of AI and neuroscience knowledge at Numenta he develops a new theory of the mind called A thousand brains.

The simplest and shortest way I can explain it is this:

The neocortex holds thousands of models of “objects” made of sensory input and reference frames. These models are learned through sensing and moving. The inference is done by “voting” between concurrent models.

Note that these are all high-level concepts that are useful to explain how it’s all supposed to work. There are no “objects” or “reference frames” in the brain - there are synapses, dendrites, cortical columns, minicolumns, grid and place cells (or at least growing evidence that they exist), axons, etc… but it’s hard to explain how intelligence works by using the “hardware” components alone. It’s like trying to explain how a combustion engine works using quantum mechanics - it’s possible, but it’s not the right level of abstraction. The first part of the book is defining this abstraction and connecting it with the different “hardware” parts of the brain.

Let’s dive into what each of these concepts means:

Models of objects

An object can be an apple, a person, a math equation, language, democracy, love, etc… These “objects” are all the same to the neocortex. The same means that the same building blocks or algorithm (inside cortical columns) is used to represent them. This is remarkable because we don’t normally think of grouping abstract things such as calculus with an apple. Remarkable as it may be, there’s a lot of evidence supporting this claim (more below).

The brain maintains models of these objects. Not one model per object, but thousands of concurrent models per object. These models are physically distributed across multiple regions of the neocortex into cortical columns. A single cortical column can concurrently hold thousands of models. In the human brain, there are an estimated ~150k cortical columns.

A useful analogy is to think of a sum of models of an object (let’s call it object-model) as a big jigsaw puzzle with 1000 pieces. Individual puzzle pieces are located in separate cortical columns distributed across the neocortex and the sum of them makes the object-model representing “math” for example.

These individual puzzle pieces are confusingly called models as well, hence the object-model term I introduced above. Let’s call this partial model: a piece-model.

The brain creates a view of the world using millions of these object-models distributed across ~150k cortical columns. Visualize millions of jigsaw puzzles randomly stacked one on top of each other in ~150k columns with a huge amount of connections between them: as far as I understand it, this is what the theory of a thousand brains looks like. It’s a mess, but if you look at the neocortex you start to think it’s not that bad.

Note that it doesn’t mean that an object-model has one piece-model in each of the 150k columns. It depends on how complex the object in question is.

Reference frames

Now let’s take a single jigsaw puzzle piece or piece-model from a single cortical column and see how it’s supposed to work. A piece-model is composed of 2 parts:

- Sensory input or features (Ex: color, temperature, sound).

- Reference frames or refs in short.

These refs are like relative cartesian coordinates of different sensory inputs. Let’s bag this concept for now and let’s dive into an example:

Imagine you have an apple in your hand, what does your brain get as input?

- There are your fingertips that have spatial coordinates relative to the rest of your body, the pressure relative to “less pressure”, the temperature difference.

- The weight of the apple felt by your nerves in your arm and shoulder.

- Your visual system observes the color difference, the corners of the apple and the different distances from your body and compared to other objects in your visual field.

The difference of pressure, temperature and distance between your eyes and the apple: these are all refs.

The example above is pretty static and while we can imagine a model of an apple from a 100ms experience of holding it, this is not how the brain builds these refs and sensory input. Instead, the brain learns both features of objects and their locations over time.

A single cortical column learns complete models of objects by integrating features and locations over time.

The brain learns these refs and features by moving the object around and observing over time. Movement appears to be a key factor of learning models.

The what (sensory input) and the where (reference frames) of each model are tightly coupled inside a cortical column. The refs are “implemented” by place and grid cells together with other parts of the cortical column. The evidence that these grid/place or “location” cells exist in the neocortex is not confirmed yet, but there is growing evidence.

One last detail I want to add about movement + perception is that the “movement” neurons that send the movement commands to the old brain (neocortex doesn’t have direct access to muscles) are also part of cortical columns and are mixed with sensory and location neurons. They are distributed everywhere around the neocortex.

Inference

The inference is done by voting between these models.

Inference, model convergence? Deciding if a chicken is a chicken. Whatever you want to call it.

Once the cortex constructs these distributed models what happens if it tries to identify an object?

Voting!

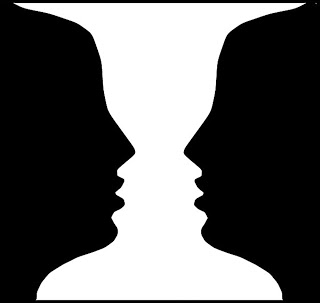

There are long-distance connections between columns, inside the same cortical region (Ex: visual) and between regions (Ex: visual and touch). I think this image of the Rubin vase here can give you a clue about what happens. Your brain tries to decide between 2 different equally valid models. What’s curious is that you can see either a vase or 2 faces, but not both at once.

More evidence to justify the theory

Again, read the book because it’s super interesting! I omitted important things about the brain and neocortex, but here are a couple of things worth mentioning:

- The neocortex looks the same no matter which region you look at, meaning that cortical columns and their structure are similar across regions. It appears Vernon Mountcastle was first to make this observation and if that’s not OG enough he proposed that cortical columns have a common neocortical algorithm.

- The neocortex looks the same, but not for all things. Language regions appear to be concentrated in certain areas and their connectivity is greater than other parts. Density may be higher, that fundamentals look the same.

- The evolution of brains looks additive - more complex organisms have bigger and more complex brains. More of the same is the successful evolutionary strategy.

- The newer the brain the “less specialized” it looks and the “more uniform” it appears and the “more of it” there is. Recall that the neocortex occupies ~80% by volume. That’s a lot of brain and it’s not cheap to run! To think that I’m using it to watch memes on the internet…

What’s next? More questions than answers!

- It appears that the “motivation” or “goals” of the brain is not set in the neocortex, but in the “old” brain and there is a constant “battle” between the two. The “old” brain wants to eat the marshmallow, but the new one has a model of you on a diet. Is this accurate? If yes, then what is the mechanism of this interaction?

- Is it confirmed that grid and place cells exist in the neocortex? It’s a key part of the theory.

- Recursion (around language and other nested concepts) was mentioned, but I’m not sure I understood how it works.

- How do location cells work with perception cells together?

- How does the voting happen technically? I get there are connections between columns, but where does the “winning” of the vote happen?

- How does prediction happen? I think I understood the basics of primed & inhibitory neurons vs un-primed neurons, but how that leads to prediction is unclear.

Closing thoughts

I’m excited about what I learned and eager to follow the reading recommendations at the end of the book. I realize that I may have misinterpreted parts of the book and there are a lot of details - I hope to correct and improve my knowledge as I discover more about the subject. There is a non-zero chance that Jeff’s theory is wrong, but his theory can be tested which is exciting!

Huge respect for having the audacity to attack this fundamentally hard problem. I’d like to express my admiration for Jeff’s persistence, he started this journey the year I was born, in 1986 and he’s still at it! Looking forward to book #3.

Finally I want to leave here a video of Jeff explaining much better what I described in this post.